1993 - Volume #17, Issue #5, Page #18

[ Sample Stories From This Issue | List of All Stories In This Issue | Print this story

| Read this issue]

Combine Converted To 4-WD Using Pickup Axle

|

|

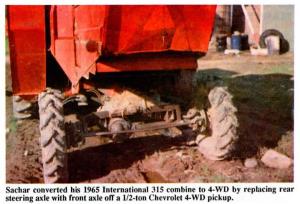

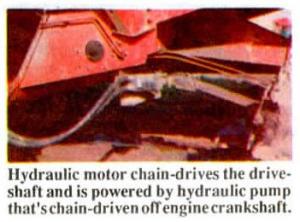

Sachar paid $100 for the front axle off a 1972 Chevrolet 4-WD pickup. The axle was equipped with lockout hubs. He turned the axle upside down and fitted it with an oscillating mount (taken from an International 105 combine) that allows the axle to pivot back and forth. He welded a 3/4-in. steel plate, fitted with a bearing and a hydraulic motor, onto the combine frame ahead of the axle and ran a 12 in. long, 1-in. dia. shaft from there to the axle's original driveshaft. The hydraulic motor chain-drives the drive-shaft and is powered by a hydraulic pump that's chain-driven off the engine crank-shaft.

"We built it because almost every year we have to fight mud to harvest corn. The difference with 4-WD is truly amazing," says Sachar. "It cost only $2,000 to make the conversion. A commercial 4-WD hydraulic assist would have cost over $10,000, but I doubt we could have even found one that fit because our combine is so old. We made the conversion in the fall of 1990 when it was really wet. We had tried pushing the combine with our 4-WD tractor, but that didn't work very well.

"We were intrigued with stories in FARM SHOW about farmers who used the front axles from 4-WD trucks to replace the rear axle and power them in various ways. We thought it would be best to power the axle hydraulically so we could more easily match the speed of the front and rear wheels. Hydraulic drive provides an infinite range of speeds.

"We tried using belts to drive the hydraulic pump, but they slipped too much so we went to chain drive. We use a vane pump that puts out 24 gpm at 1,200 psi and 2,000 rpm's. However, we had to gear it down because the combine engine runs at 2,700 rpm's. We put a bigger sprocket on the pump than we put on the crankshaft. We also installed an oil cooler and plan to install a much larger oil reservoir.

"We use a variable speed valve in the cab to regulate the flow of oil to the hydraulic motor so that we can vary ground speed. A pressure gauge is mounted on the input line of the valve. The valve has flow control, directional control, and pressure control all in one package.

"The operator depresses the foot clutch, selects the gear and speed, and turns the valve to the right (forward) until pressure comes up to 100 to 200 lbs., then lets out the clutch. He then adjusts the valve until there's 300 to 400 lbs. pressure on the gauge. This supplies a small amount of torque to the steering axle. It's very responsive. When-ever the front drive wheels start to spin, the pressure automatically builds up to add more torque. If the going is really bad, we turn the valve up to 1,000 lbs. of pressure. To back up, the handle is turned to the left.

"We used the smallest possible sprocket on the motor and the largest possible sprocket on the driveshaft in order to deliver as much torque as possible to the wheels. The Char-Lynn hydraulic motor cranks out 135 ft.-lbs. of torque at 900 psi. The sprockets boost the torque by a factor of four and the axle differential by a factor of 3.5. We can spin the tires at 950 psi.

"We chose the 1972 pickup because it has a rigid axle that always keeps both of the combine's rear wheels on the ground at the same time. Floating axles found on newer pickups wouldn't work.

"We replaced the original 7.50 by 18 steering tires with new 9.50 by 24 6-ply tractor tires that we mounted on 8-hole wheel rims salvaged from an old corn picker. We cut out the centers on two 6-hole Chevrolet pickup wheel rims and welded 8-hole repair rings onto them. Then we welded 9/ 16-in. wheel studs into the repair rings."

Contact: FARM SHOW Followup, John Sachar, 9937 Ivareh Rd., Cranesville, Penn. 16410 (ph 814 756-3975).

Click here to download page story appeared in.

Click here to read entire issue

To read the rest of this story, download this issue below or click here to register with your account number.