The energy wasted in a car or truck as it decelerates, idles or brakes has become, with the energy crisis, an automotive engineer's oil field. At the University of Wisconsin, a research engineer who began digging into the subject several years ago, now claims to have "struck it rich" with a car partially powered off that waste energy.

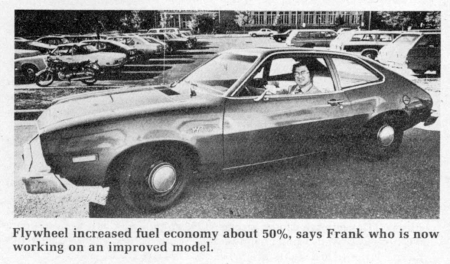

Andrew Frank's flywheel car -- a Ford Pinto outfitted with a 200-lb. steel flywheel spinning in a vacuum-sealed chamber beneath the engine -- has achieved more than a 50% increase in fuel economy. Acting somewhat like a brake, the flywheel is spun into action by deceleration and braking, as well as the car's engine. Once the flywheel reaches a certain velocity, the car's engine shuts off automatically and the flywheel, tied into the Pinto's drive train, alone powers the car. At idle, the frictionless flywheel, burning no fuel, may be the car's only moving part.

"The flywheel design lets you run the car at one speed for the highest efficiency. Once the flywheel reaches a certain velocity, the engine shuts off," Frank, an associate professor of engineering, told FARM SHOW.

"We did well with this prototype, but with top-flight components, we expect to be able to achieve a 100% increase in miles per gallon," says Frank. He has received a grant to build an improved flywheel model and notes that at least one car manufacturer, Volvo of Sweden, is already working on the concept.

"We had three goals to achieve with the flywheel design. First, to eliminate all idling and engine deceleration, since they use gasoline for no useful purpose. Secondly, to only operate the engine at its most efficient speed. And thirdly, to recover the energy used for braking," Frank explained.

The flywheel energy storing concept -- not a new idea, as anyone familiar with early farm engines remembers -- is especially suited to stop-and-go urban driving, but Frank says it's also promising as a power booster. "For farm machinery, once you get the flywheel spinning on a big-engined machine, it would take little power to keep it spinning. Yet when needed -- in muddy fields, for example -- it could be engaged for an extra burst of power," he explained.