Nebraska farmer Emil Rosno, of Fullerton, is an alternative farmer in every sense of the word -- except the stereotypical one.

He chose an alternative method of farming and an alternative crop in hopes of finding, among other things, an alternative to the financial ruin many other farmers are experiencing.

However, Rosno is not what many people think of as an alternative/organic farmer. He doesn't have long hair, wear beads or live in a tepee.

"People, when they hear organic, they think 'oh my gosh, one of those guys' It can really turn a lot of people off," he said.

Rosno, who has been farming since 1952, simply became concerned about nutrition, health and dumping chemicals on his neighbors downstream. He also became concerned about keeping his family farm afloat financially in an increasingly difficult economic climate.

Alternative agriculture is helping Rosno accomplish all of his goals. Rosno's crop is high lysine corn. It is higher than normal corn in most amino acids, especially lysine.

According to Rosno, it is also more digestible. "Normal corn is about 70 percent digestible. This is probably 90-95 percent digestible and the rest is fiber," Rosno said.

When high lysine corn was first discovered in Colombia, South America, it was seen by some as an excellent method for boosting nutrition in cattle, Rosno said. "At that time there wasn't the interest in human nutrition that there is now, so they went with the livestock."

Tests at the University of Nebraska have shown high lysine corn yields are nearly equal to those of regular corn hybrids, but have a much higher food value. Rosno's own son has found his lambs gain faster when fed the corn and that dairy cattle "really soup up" on it.

Still, Rosno said, there wasn't widespread acceptance of the corn, primarily because it was new. "There is a stubborn attitude on the part of many farmers who feel they must use the same products as their ancestors and their children should use them too."

Eventually all but a couple of seed corn companys gave up research on high lysine corn and carried only one or two token hybrids.

But Rosno persevered. If farmers who used the corn for feeding stock have good results with it, it ought to be good for humans too, he reasoned. "It seemed just stupid to be feeding the livestock better than the people."

So Rosno developed his own method to process the corn for humans.

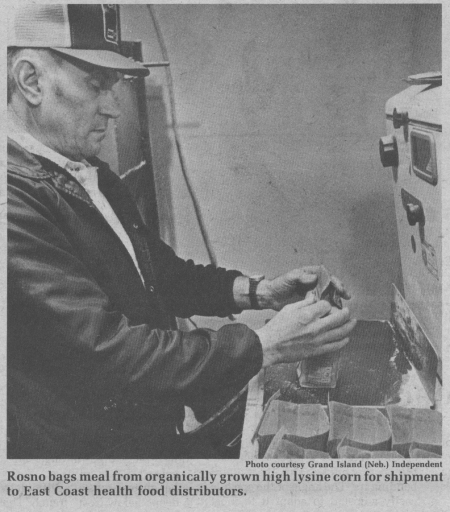

With a tiny grinding operation in a former dairy barn, he now hand packages high lysine corn meal for shipment to health food distributors on the East Coast.

He credits the high lysine corn meal operation with keeping his farming operation solvent: "I guess if it wasn't for the corn meal we'd be broke."

The work is not easy and Rosno and his wife, Deloris, perform almost all of it themselves.

But there is money in it. "If the reward is there financially, you do a lot of things," Rosno said.

He declined to say how much the small business earned during the past year, but noted it was more than he made farming.

Before Rosno began selling the high lysine corn for human consumption, he had already made one change in his farming operation that was necessary for that market.

"All our stuff goes to health food stores and they demand organically grown," he explained. This is the eighth year that his crops were grown without the use of chemical pesticides or fertilizers.

Initially, concern about his family's health caused a conversion to organic farming. Rosno said he was concerned because so little was known about the long-term effects of chemical use.

The effect that buying chemicals had on his farm finances bothered Rosno too, he said.

Rosno noted that without chemicals, his yields are about two bushels per acre less than they would be with chemicals. His costs are also less. As long as corn prices don't get too high, something not likely in the forseeable future, Rosno feels he is saving money and a lot of it.

He also feels better about farming: "Now when you farm like this you don't have to worry about poisoning somebody downstream."

Rosno decided to switch to a system of rotations with alfalfa and oats to gradually restore the organic matter, enzymes and beneficial earthworms in his soil that were reduced by years of chemical use. By discontinuing applications of anhydrous ammonia, soil compaction problems were reduced as well.

Some of Rosno's neighbors guffawed when Rosno switched to alternative agriculture: "I think they think we're crazy, but some of them aren't in business anymore. Times are changing. As economic conditions worsen more people will be willing to look at alternative ways to make a profit and stay in business.

"Cutting chemical costs is one way. Growing alternative crops, not just high lysine corn, but many other foods, is another.

"I think this is something people are going to have to look at, not just growing corn, or whatever they've been growing, for 20 years."

However, Rosno admitted that alternative agriculture is not an easy, get-rich-quick scheme. Plenty of hard work is involved. And there are frustrations, such as the lack of a developed market or a local market of much consequence.

But Rosno is confident. The growth in his business has been encouraging. And, according to Rosno, he is making money and feels good about what he's doing and that's a claim not everybody can make.

(Reprinted with permission from the Grand Island (Neb.) Independent.)